Wheels

Written 2025-09-19

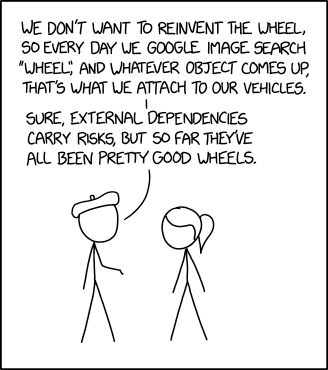

I've personally never understood why people discourage reinventing the wheel, specifically in the case of software.

I mean, I understand it from the perspective of people just starting out with programming- if you don't know what you're doing, i.e. you don't realize wheels exist, you might spend a ton of time making a square one.

But if reinventing the wheel is so awful, why are there so many different wheels that seek to achieve the same thing?

Maybe it's because the wheels we already have aren't all that great.

Compiler wheels

Look at LLVM and QBE for example- both of these are compiler backends, used for generating an intermediate representation (basically a low level meta-language that can be efficiently compiled into optimized assembly code). LLVM's intermediate representation can be compiled into numerous target instruction sets- x86-64, ARM, M68k, and MIPS to name just a few- and is used for code generation with the Clang C and C++ compiler, the Rust compiler, the Zig compiler, and numerous other programming languages. At this point, LLVM is becoming a bit of an industry standard for new, "serious" compiler projects.

LLVM isn't without its problems, however. For one thing, it's one of the largest projects on GitHub, having over 2 million lines (around 1.3 GB) of source code. The source repository is, of course, quite slow to compile- and compilers that use LLVM often have slower compile times in general, according to the creator of the C3 compiler, Christoffer Lernö, who points out that the object-oriented design of the compiler backend's C++ code results in an abundance of heap-allocations. Lernö also notes the existence of mandatory undefined behavior, and mediocre documentation.

From my personal experience, I tried setting up LLVM as the compiler backend for a language I've been trying to develop for a long time. After spending a couple weeks just trying to get LLVM set up properly and integrated with the project, I was burnt out and gave up. The limitations of the documentation were my main point of struggle- as I was using LLVM not in an "industry" environment, but simply to learn about compiler engineering, this made me turn away from the project- compiler design is already difficult enough to learn; adding LLVM simply made the learning curve too steep.

QBE does exist as an alternative- it boasts being able to "provide 70% of the performance of industrial optimizing compilers in 10% of the code", and uses an incredibly similar intermediate representation to LLVM's. Its codebase is much simpler, and the example projects are (relatively) easy to understand, at least for me. Compared to LLVM, however, it cannot support as many architectures (as of today, only amd64, arm64, and riscv64). Its documentation is much simpler, but does appear to neglect to mention any mandatory undefined behavior within the intermediate representation, and whether this is because there isn't any or because it simply isn't mentioned is unclear.

Lernö points out that upon drawing these conclusions, it isn't surprising that projects will consider just writing their own compiler backends, adding another wheel to the ever-growing pile.

Web development wheels

My Django story

In the beginning of the latter half of completing my bachelor's degree in computer science, I had to take a Software Engineering course, where we used Django to develop some rudimentary web-apps on tight deadlines (2 weeks to a month). At the time, using Django made sense- all of us were intimately familiar with Python, and Django had a lot more "out-of-the-box" features than other tools we had used, like Flask.

Saying that I had an immensely difficult time would be an understatement. I was already going through a lot at the time, and adding the stress and disillusionment that came from this course led me to begin seeing a therapist. By the time I had completed and passed the course, I had made an informal vow to avoid touching anything written in Python at all costs- and the thought of doing any sort of corporate web-development left such a bad taste in my mouth that I was considering leaving computer science altogether (and going back to what I had originally wanted to get a degree in: anthropology). I didn't, but mostly because I was too far down the computer science degree pathway already.

What I loathed so much about Django was that, in keeping with the wheel metaphor, Django was a wheel composed entirely of hundreds of other wheels, all buried in the documentation. I mentioned in the very beginning that people who are new to a piece of development software can get overly caught up in "reinventing the wheel," but oftentimes going down this route felt easier (and more educationally enriching, which you'd think would take priority in a college course) than combing through the immense documentation to find the one built-in solution for what I was trying to do.

This neglects to mention the pains of dealing with and learning new HTML templates, CSS frameworks, deploying through Amazon EC2, desperately trying to maintain decent version control for this every-growing tower of wheels, etc.

The web as a whole

I'm not the only one who feels this way about web development, and the fact that web development tools are increasingly being used in unnecessary contexts, the ever-growing number of web development frameworks, and the needless complexity that all of these new wheels bring in can be incredibly overwhelming.

Some go so far as to say the web itself is broken, not just from the added bloat to websites, but as a result of increasing paywalls, advertising, required sign-ins, search engine optimization, and, now, artificial generative intelligence.

It only makes sense that when people get frustrated with a wheel, they make their own wheels. There are replacements and alternatives for the web itself, some of which are quite old, such as Gemini and Gopher. Sites like Neocities seek to revive the early days of the internet, when things were less complex and much more personal.

Your wheels

Every piece of technology that we use can be looked at as thousands of wheels, many of which are the direct results of being frustrated with wheels that already existed.

I see no reason why reinventing the wheel is still such a taboo in this situation- tech stacks can be complicated and messy, and if you've been a developer (or even just a casual user) you've probably found some piece of software that, for lack of a better word, sucks.

Reimplementing it for your needs, i.e. reimplementing the wheel, if you have the time to do it, can not only be an enriching exercise that improves your skills as a developer, but also can result in creating something that you actually enjoy using.

For example, my website is the result of me deciding to completely reinvent markdown from scratch (see letdown) and then creating a very Spartan static site generator that can convert my blog posts into clean and simple HTML, with a basic yet pretty layer of CSS all in a single, short stylesheet.

All of this only took me a weekend. Think of how much you can do with, say, 9 months?